A tissue of mayflies - the world's thinnest paper

Japan, although being the world’s technology giant, is almost unique in its respect for tradition. Its unique culture and heritage is highly valued, and none more so than its ancient paper industry. Such is the world’s respect for Japanese paper’s heritage, Washi (Wa-Japanese Shi-Paper), is now one of UNESCO’s Intangible cultural heritage objects.

The Origins of Japanese Paper

Paper making began in China around 150 B.C. Using hemp as it’s material source, the paper’s initial use was thought to be for wrapping, due to the product being too rough to write upon. Having identified a use beyond this, China’s paper makers, encouraged by court officials, refined their product to make it suitable for the writing of official documents in around 105 A.D.

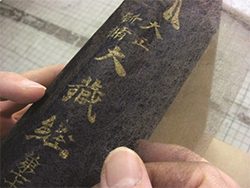

Paper making officially arrived in Japan in 610 A.D., it’s believed, introduced by a travelling Korean Monk who passed on his knowledge of the techniques he had learnt over the sea. As in China, the original demand for paper was for Japan’s official documents, which increased under the reign of Prince Shotoku (574-622 A.D.). Buddhism was encouraged under his reign, and as such, the copying of Sutras (religious texts) required a reliable paper manufacturing source. Demand was such that the Japanese paper making industry blossomed and was actively protected by the country’s rulers. It would take Europeans another 400 years to develop their own paper making methods, by which time the Japanese paper making industry was well established.

Due to its labour intensive manufacturing process, traditional Washi became prohibitively expensive in the late 1920s where machine-made paper all but ruined many family run paper making businesses in Japan. But it is in that hand-made process that much of the uniqueness in the paper is built, and the industry survived through a handful of manufacturers. Japanese papers are generally made from Kozo (mulberry tree bark), Gampi (bark), or Mitsumata. The finished paper is structurally much stronger than Western papers made from wood pulp, and it is this resilience that has ensured the product has a future. It’s said that 100% Kozo paper can have a life that spans over 1000 years.

Why Japanese Paper?

Sometimes referred to as tissue, Japanese paper, has many uses, particularly in the area of conservation and preservation. The higher strength of the fibres in Japanese paper allow stock weights far lighter than those of wood pulp papers. We now stock a Japanese paper which has a weight of only 1.6gsm.

Japanese paper is ideal for interleaving, surface repair, surface protection, framing and doubtless many other conservation uses. Chlorine can remain in paper causing it to yellow over time, but provided no acidic elements have been used in the bleaching process, Japanese papers are acid-free. As the fibres of Japanese Paper are interlaced at random, the paper is incredibly flexible and can be worked with when wet, making it excellent for repairs in paper.

Tengu – The World’s Thinnest Paper

Tengu Japanese paper, or tissue, is Tosa Tengujo (also spelt Tengucho), in its homeland it can be referred to as ‘wings of a mayfly’, which paints a fairly accurate picture of its fibre structure. Designed to provide strength and protection, Tengu paper is used around the world in a range of preservation applications. Machine-finished to achieve weights from only 1.6gsm, making it the thinnest paper in the world. Tengu is ideal for interleaving, surface repair, surface protection and doubtless other uses. Unlike many other Washi, Tengu is not bleached using chlorine and is instead washed in a slightly alkaline solution to achieve a uniform colour.

Manufacturing of Tengu Japanese Paper

Kozo is carefully selected and cooked to remove pectin and lignin leaving only cellulous fibres.

The cooked kozo is then cleaned in running water as it was done hundreds of years ago. Scratched or damaged pieces are removed as they can cause dark patches which cannot be bleached. The cleaned fibres are disentangled by hand and then bleached to achieve a uniform colour.

Fibres are mixed in a solution containing 'neri' and flowed into the paper making machine. The machine automates, but replicates, the actions in handmade paper production to achieve an even distribution of fibres. The fibres are now a sheet which is dried slowly and rolled. Finishing the rolls is a carefully managed process to ensure the paper remains wrinkle-free. The meticulous nine-stage manufacturing process results in a finished paper that is unrivalled in its weight and quality.

What’s a deckled edge?

Traditional hand-made Japanese papers have a deckled edge. This is the rough unfinished edge of the paper sheet where the fibres have ‘seeped’ under the deckle in production. A deckle is a wooden frame used to shutter an area, controlling the size of the paper sheet produced. Deckled edges can now be replicated in machine made papers, our Tengucho tape has two machine made deckled edges.

Preservation Equipment stock a wide range of Japanese papers suitable for conservation purposes. Click here to view our range.